E=MC2

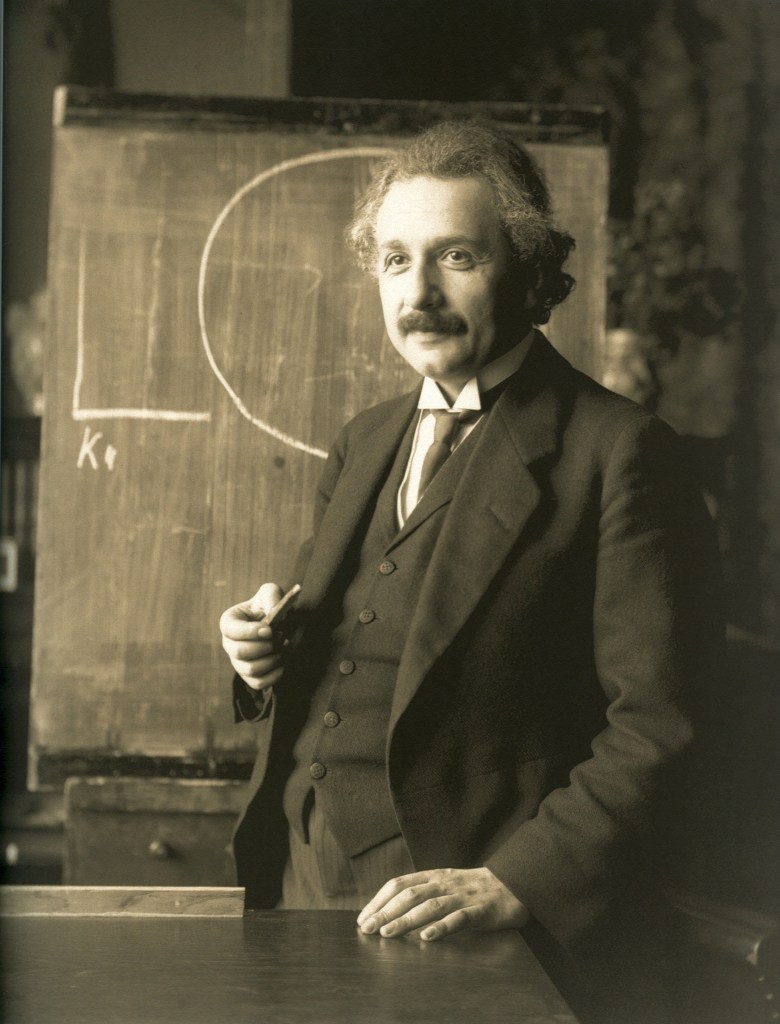

The most famous equation in all of physics was developed by arguably the best-known scientist ever, Albert Einstein. While that equation had to do with calculating energy, Einstein was not just a student of theoretical physics, but also a great study of how to live a good life.

In a recent article on The Big Think, Ethan Siegel explores Einstein’s 7 Rules for a Better Life. Taken from a recent biography on the great scientist, Siegel shares life lessons which served Einstein well. For example, take Rule #3, Have a Puzzle Mindset.

Einstein was pretty much the prototype individual for someone who viewed every difficulty he faced as a puzzle to be solved: in physics and beyond.

Consider his oft-misunderstood but most famous quote, “Imagination is more important than knowledge.” While many people had looked at the puzzle of objects moving near the speed of light before — including other geniuses like FitzGerald, Maxwell, Lorentz, and Poincaré — it was Einstein’s unique perspective that allowed him to approach that problem in a way that led him to the revolution of special relativity. With a flexible, non-rigid worldview, Einstein would easily challenge assumptions that others couldn’t move past, allowing him to conceive of ideas that others would unceremoniously reject out-of-hand.

Rule #4 carried on this thought by sharing the advice to: Think deeply, both long and hard, about things that truly fascinate you.

Over the course of his long life, Einstein received many letters: from those who knew him well to perfect strangers. When one such letter arrived on Einstein’s desk in 1946, asking the genius what they should do with their life, the response was as astute as it was compassionate. “The main thing is this. If you have come across a question that interests you deeply, stick to it for years and do never try to content yourself with the solution of superficial problems promising relatively easy success.”

Learn about the remaining five rules by clicking over the The Big Think website.